Hot new insights on pioneer transcription factors are reviewed by Barral and Zaret in the latest Trends in Genetics.

Cells adopt new roles during cell differentiation or tumor disregulation, and it is well known that this change is guided by master transcription factors, known as pioneer factors (PFs) that can open/activate regulatory elements, active promoters and enhancers, and they have the ability to do it in condensed chromatin. Barral and Zaret review new results on the function of those key proteins, some as recent as this year. I will cite several.

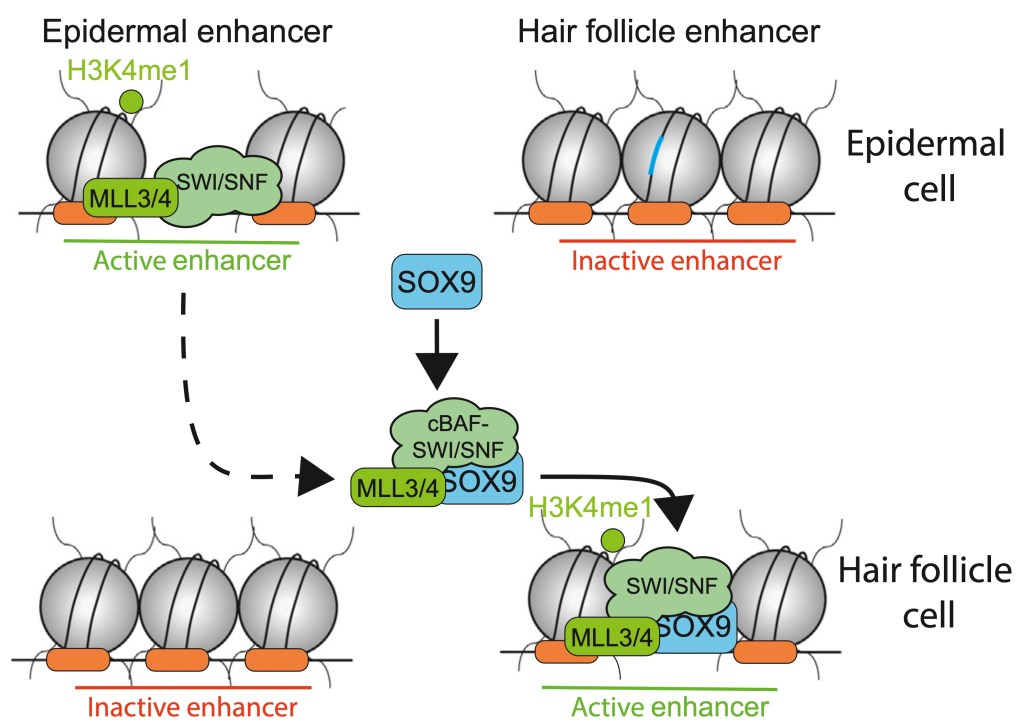

While PFs open/activate regulatory elements, they can also deactivate other ones. SOX2 recruits activating chromatin factors by “scavenging them” from active sites and depositing them in sequence-specific locations of enhancers it activates. This scavenging is not sequence-specific. Presumably, the enhancers that survive must be subsequently visited by transcription factors that opened them, and receive the protective chromatin factors back. Those transcription factors do not need pioneer ability because the active status of “victim” enhancers does not vanish instantly. Such mechanisms explain different levels of marking/occupancy that we see in assays like ChIPseq and different expression levels of genes, i.e. modulating the gene expression.

However, other PFs like PU.1 are shown to bind to DNA first, and recruit activating chromatin factors later, with the former process measured to be much faster than the latter. Moreover, Barral and Jaret discussed several other different types of enhancer closures driven by PFs.

Another recent finding is that the ability of PFs to access “inaccessible chromatin” may depend on its subtype, e.g. PAX7 can access heterochromatin marked with H3K9me2 but not heterochromatin marked with H3K9me3.